Women's Liberation and Peace

National Women's Conference (1977)

Women's Pentagon Action

Abortion Rights Demonstration

Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and

Justice (Seneca)

____________________________

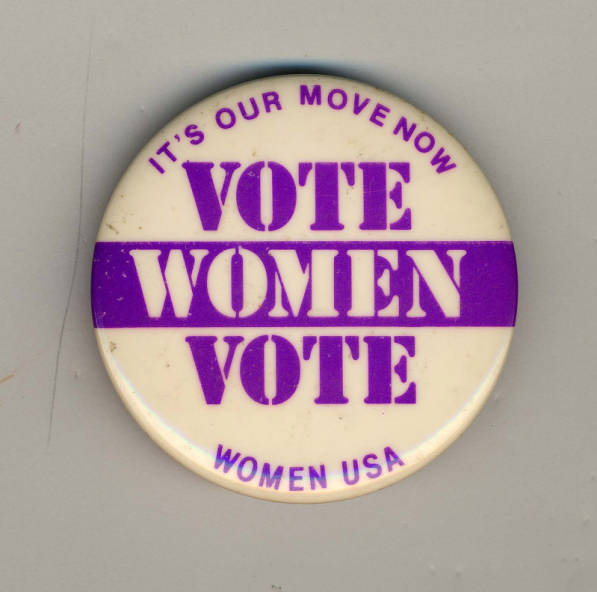

Women's Liberation (1960s, 1970s,

1980s)

In the years after World War II increasingly

women entered the paid work force, even after marriage, despite

ubiquitous discrimination and cultural pressures to remain in the home. A

variety of political and cultural shifts in the 1950s revitalized

social awareness of women’s roles and the need for a new emphasis on

women’s rights. President John F. Kennedy’s Commission on the

Status of Women (1960) attempted to document discrimination against

women in the work place. Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique

(1963) was one book published early in the 1960s which helped focus

attention on the plight of American women. Friedan’s work a

powerful and controversial book exposing the mass discontent of many

middle-class women and challenged post-war ideas of domesticity.

Feminists who had long fought for the Equal Rights Amendment and other

rights for women were able to lobby successfully for the inclusion of

Title IX in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Title IX was a huge

victory for women’s rights, making it illegal for institutions or

corporations receiving federal funding to discriminate based on sex.

The 1960s were an era of social consciousness, political activism,

reform, and radicalization and women were significant activists in the

growing anti-nuclear movement, the Civil Rights Movement and the

protests against the Vietnam War. Women’s Liberation was a

broad-based movement of radical and progressive women, and fostered

female activism. In 1965, feminists including Betty Friedan,

Gloria Steinem, Flo Kennedy, and many others, founded the National

Organization for Women (NOW), an influential, progressive organization

focused on fighting for equality for women in all aspects of U.S.

society. During the 1970s and early 1980s NOW led the fight for the

Equal Rights Amendment to the federal constitution which would have

outlawed discrimination based on sex. Only 35 out of the needed 38

states ratified the amendment, and the ERA did not become law.

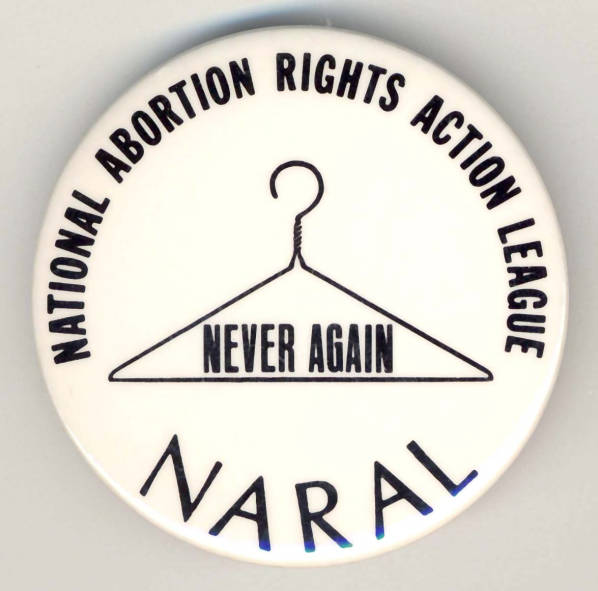

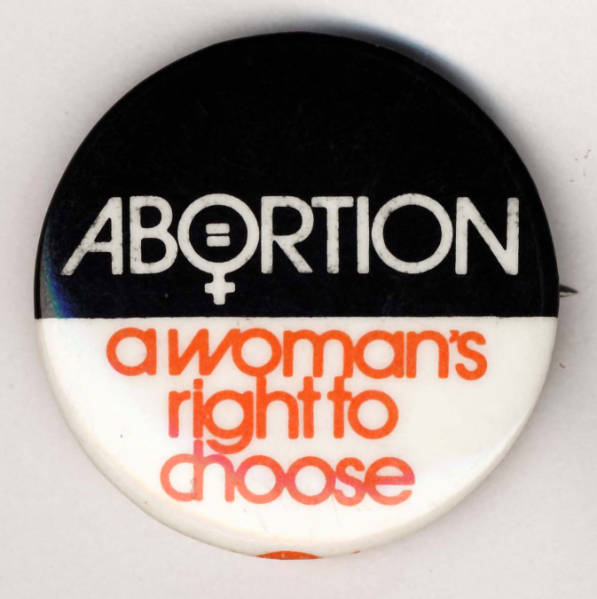

Issues women raised in this “Second Wave” of feminism grew to include

equality in education and the workplace, marriage, legalizing abortion

and reproductive rights, questioning of male militarism, and female

sexuality.

More radical feminists, who believed that a transhistorical and

transnational patriarchal system primarily oppressed women were active

on a broad range of issues outside of legislative and institutional

politics, especially after the late 1960s. Throughout this period

Dorothy Marder continued to be active in progressive and radical

feminist circles, as well as more traditional women’s organizations such

as Women Strike for Peace.

Mary C. Lynn, Ed. Women’s Liberation in the Twentieth Century. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1975

National Women’s

Conference, Houston Texas 1977

The re-newed fervor of women activists in the 1960s and 1970s

forced the presidential administrations of John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson,

Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter to establish various federal commissions

to explore the issues of equal rights for women. President John F.

Kennedy created a Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in the

1960s, and President Lyndon Johnson appointed a Citizen’s Advisory

Counsel on the status of women. . The United Nations declared 1975

to be “International Women’s Year”; and later declared 1975 to 1985 the

Decade for Women. When he became President, Jimmy Carter appointed

Congresswoman Bella Abzug to head the Commission. Abzug later proposed a

National Women’s Conference.

Two years later, the

first National Women’s Year Conference was held in Houston, Texas.

Women from all 50 U.S. states and territories attended. Notable

women in attendance included Grace Paley, Betty Friedan, Maya Angelou,

Corretta Scott King, Bella Abzug, Margaret Mead, Elizabeth Holtzman, and

among others. Later, Dorothy Marder would write:

It was the first time in

American history that so many women from so many different

backgrounds…were able to assemble together in one place to talk and to

hear each other…We connected with each other in a profound way. (55)

Conservative women

and men were also a presence the Conference, including anti-ERA activist

Phyllis Schlafly and her supporters, pro-life supporters, the Ku Klux

Klan, American Nazi Party, and the all-white delegation from Mississippi

(a state with an African American population of over 36% in 1970).

A National Plan of

Action was voted on at the Conference proposing action on important

national women’s issues, such as domestic abuse, welfare, Equal Rights

Amendment, disability, minority rights, reproductive rights, and

education. 25 of the 26 resolutions of the National Plan of Action

were passed.

Dorothy Marder

documented this historic event by photographing what she calls, “the

‘ordinary’ woman, who, of course, was extraordinary”(50) who attended

the conference. Attending the Conference was particularly influential

for Marder’s own personal and political growth. She wrote,

“Houston was indeed a turning point for me. Although I had

photographed dozens of conferences in the [19]70’s, this conference had a

very special meaning for me.”(56) Marder was particularly touched by

the testimonies at the Conference of lesbians oppressed “at work, in

school, in the military…fears of being ‘found out’ by husbands during

divorce proceedings… [and] losing their children.” (56) And she

found empowerment at the Conference in the community of women “all

feeling free to be who [they were]” (57).

Marder, Dorothy. “Houston: IWY National Women’s Conference 1977.”Dorothy Marder Collection,Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Folder: Life Experience Portfolio for Fordham University, 1989.

Mississippi Census Data: <http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0056/tab39.pdf>

___________________________________

Bella Abzug, Rosaline Carter. Betty Ford, and Lady Bird Johnson, unidentified, Maya Angelou (standing left to right)

Event: International Women Year National Conference

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - 735

6.5" x 9.5"

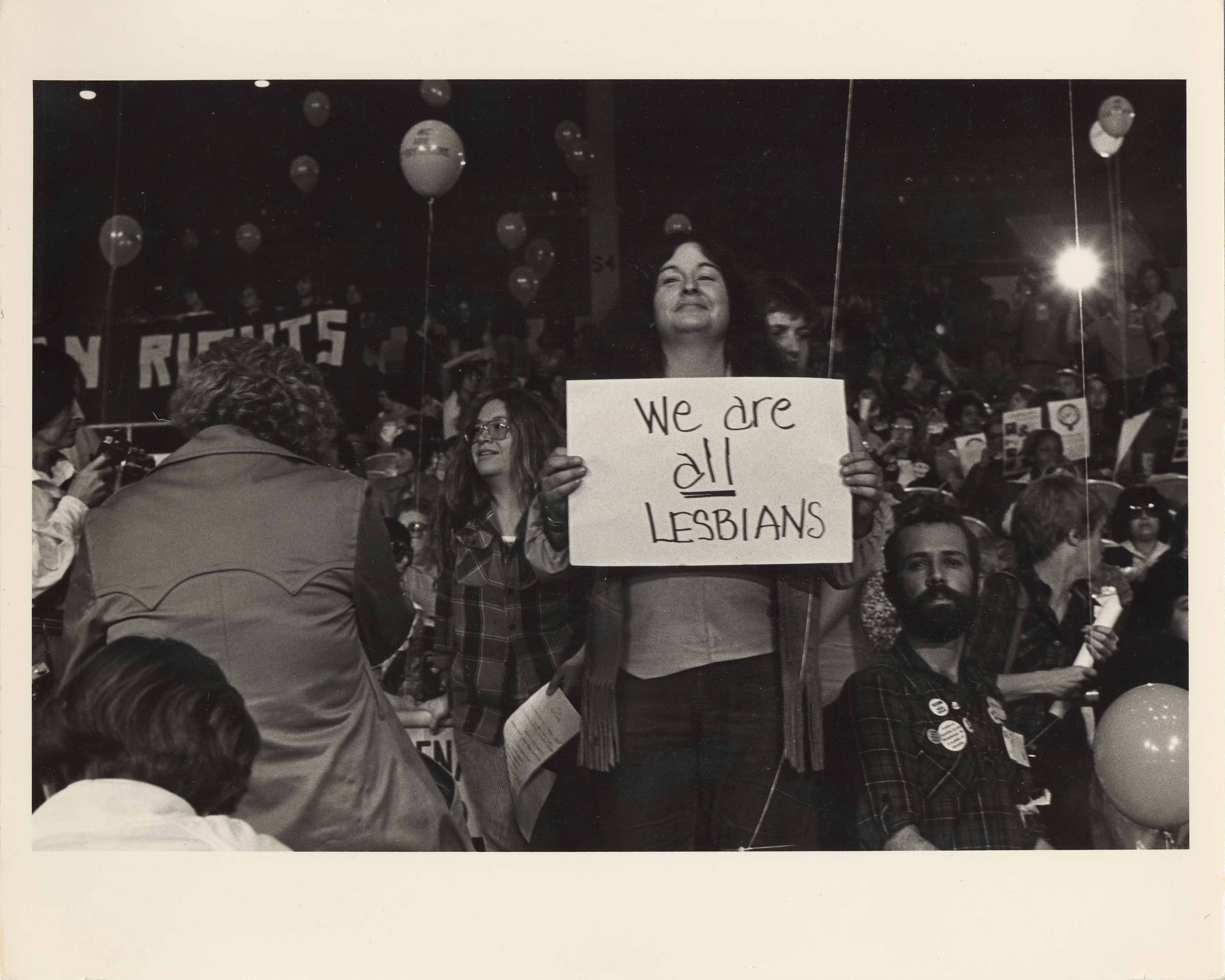

"We are all lesbians"

Event: International Women Year National Conference,

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - 735

6.5" x 9.5"

Note

After the National Women’s Conference (1977)

Marder prepared a spread for a liberal women’s magazine, The

Feminist Bulletin, and included this photograph. However, the

editor objected to publishing this image because of its homosexual

content. Marder, in turn, refused to let her other photographs

from the Conference be published without this photograph.

Marder explained to the editor that the word lesbian had been used to

oppress all women, who “allowed [themselves] to be strong, independent,

assertive, and yes, aggressive.” (57) To embrace the word

lesbian is empowering for all women because at its core it

means a woman who loves other women (57). This withdrawal of her

photography was Marder’s first public act for lesbian rights and an

early coming out experience for Dorothy Marder herself.

Marder, Dorothy. “Houston: IWY National Women’s Conference 1977.”Dorothy Marder Collection,Swarthmore College Peace Collection, Folder: Life Experience Portfolio for Fordham University, 1989.

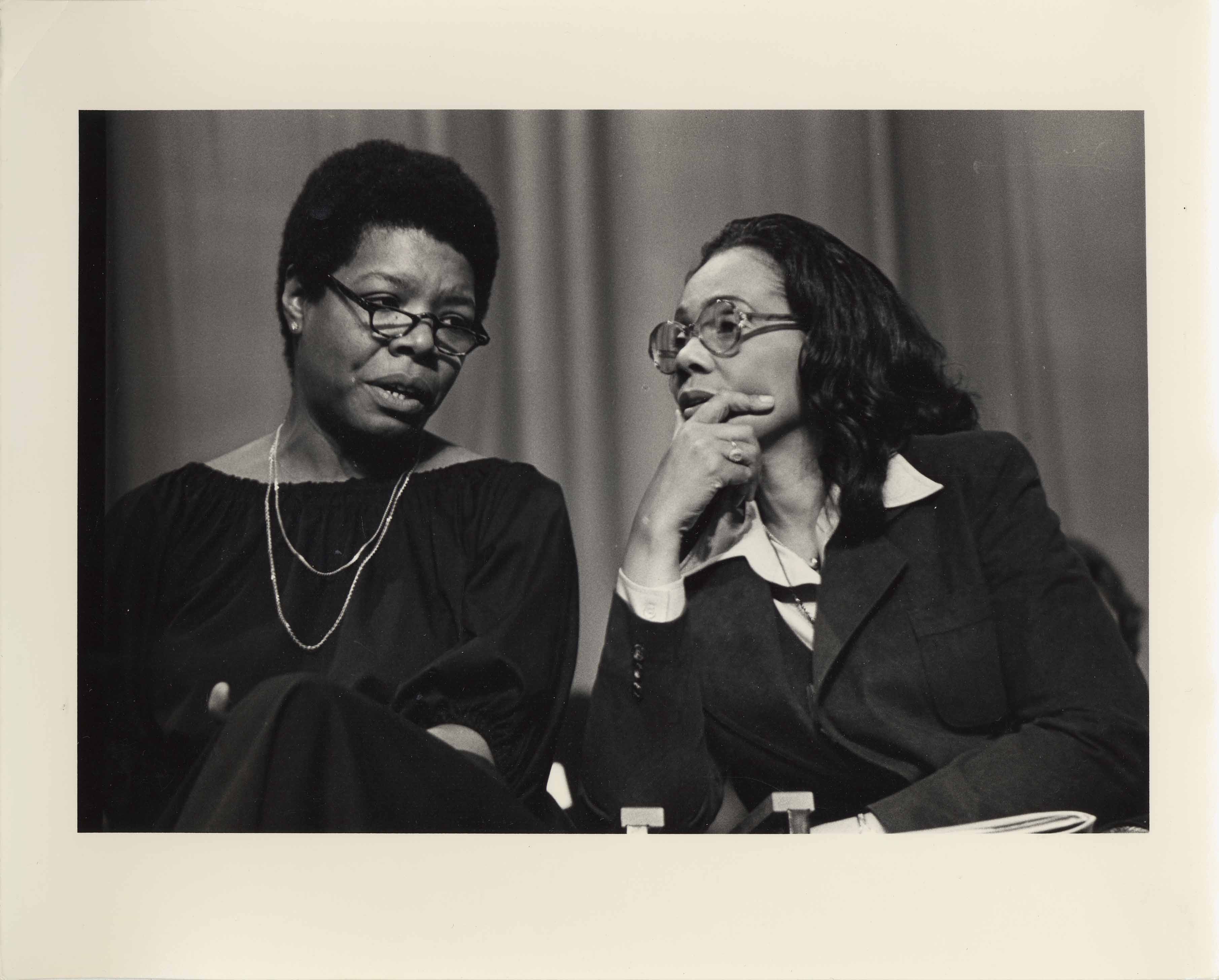

Maya Angelou and Coretta Scott King

Event: International Women National Conference,

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - 735

6.5" x 9"

Event: International Women Year National Conference

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - 735

7.5" x 9.5"

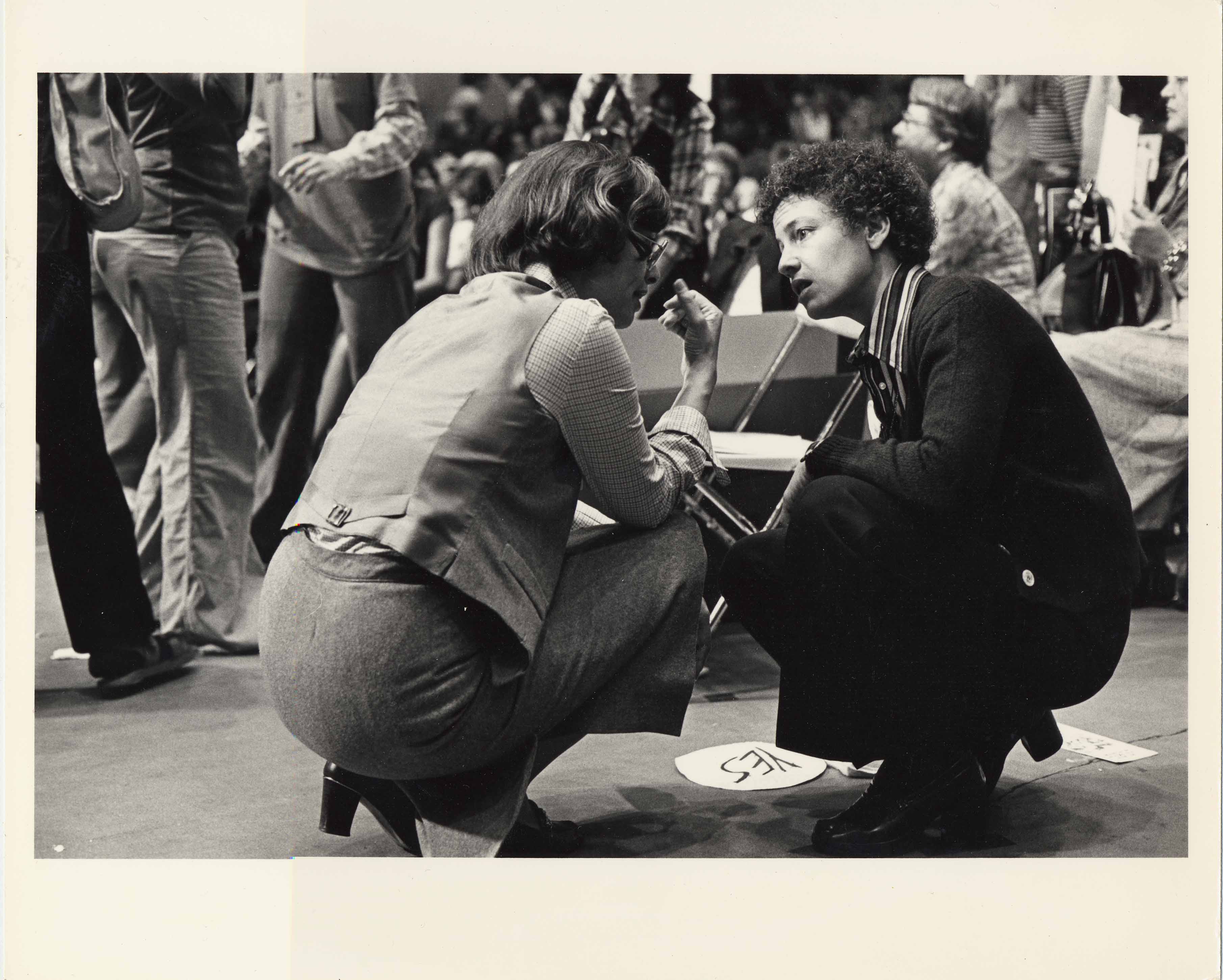

Event: International Women Year National Conference,

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - D 735

7.5" x 9.5"

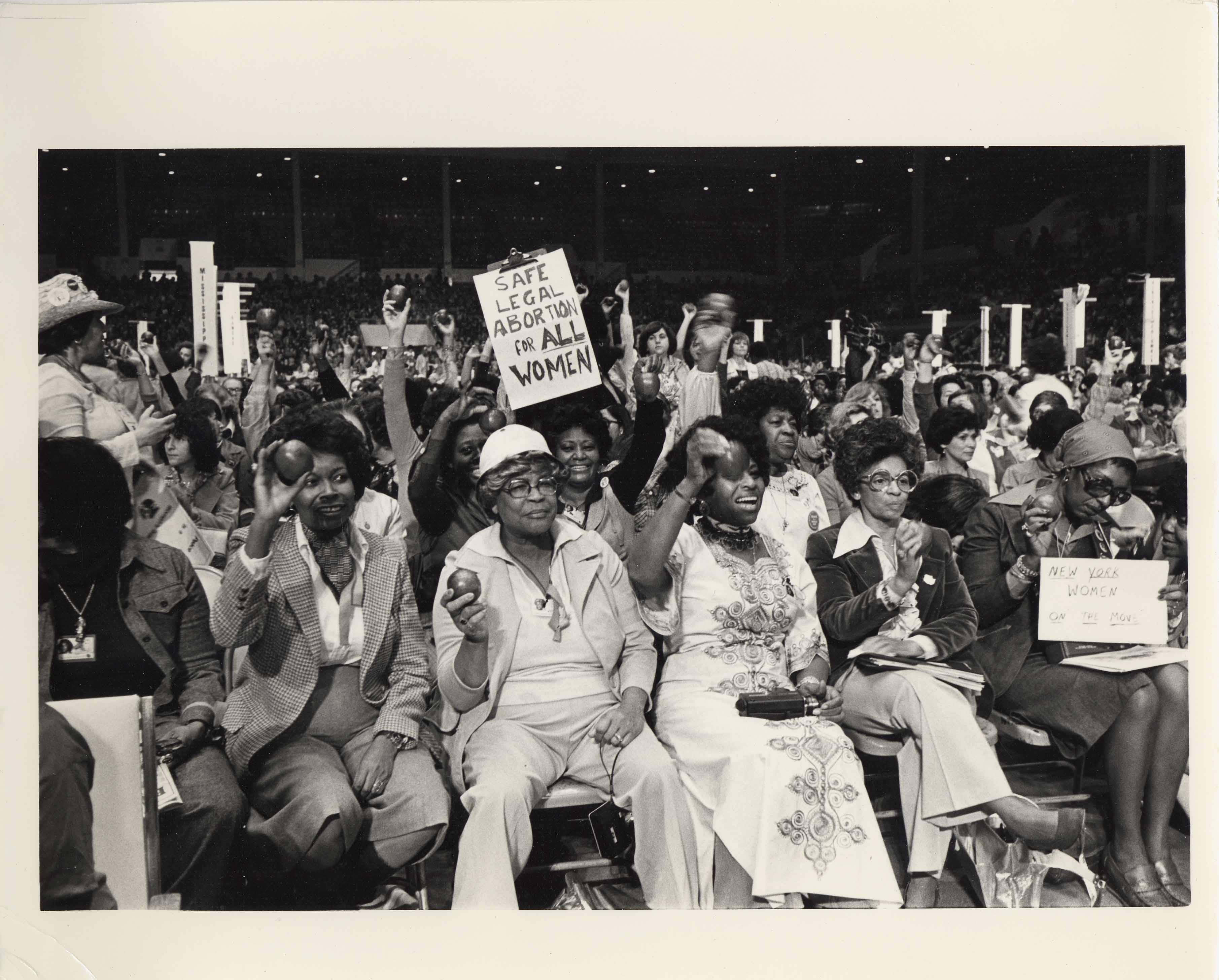

Women From New York

Event: International Women Year National Conference,

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - D 735

6.5" x 9.5"

Event: International Women Year National

Conference,

Houston, Texas

November 18-21, 1977

Prints D 715 - D 735

6" x 9.5"

Women’s Pentagon Action

November 1980 and November 1981

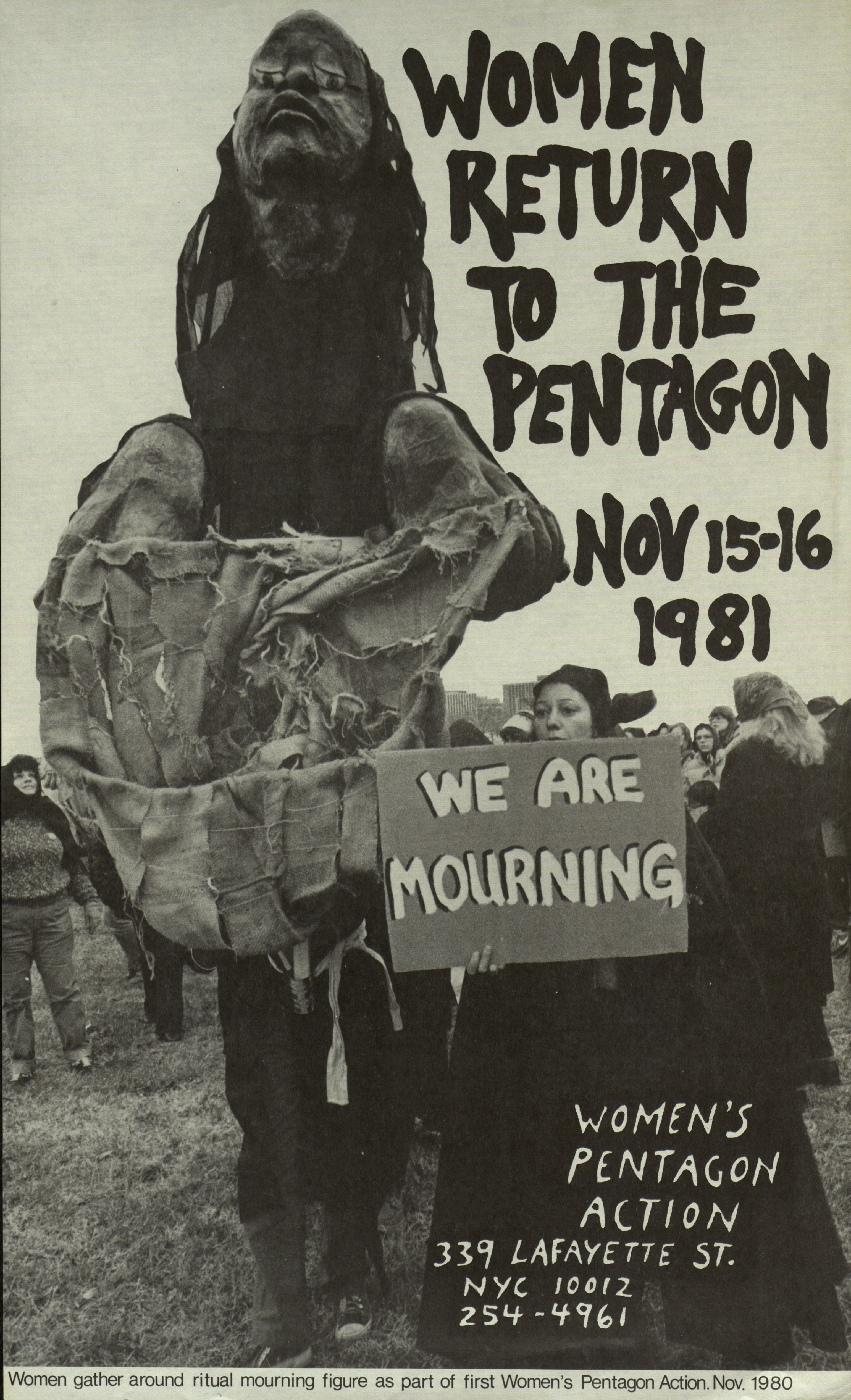

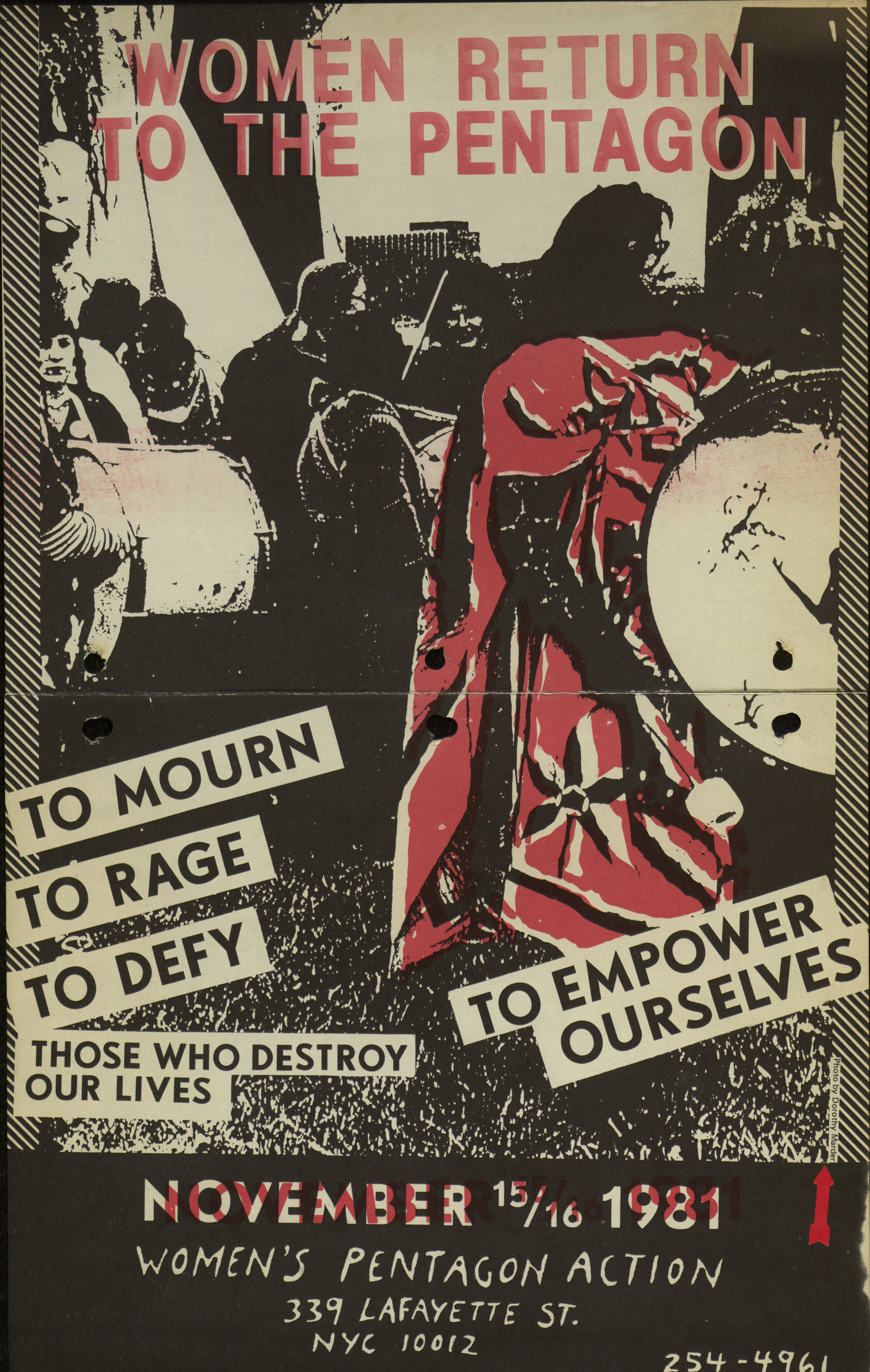

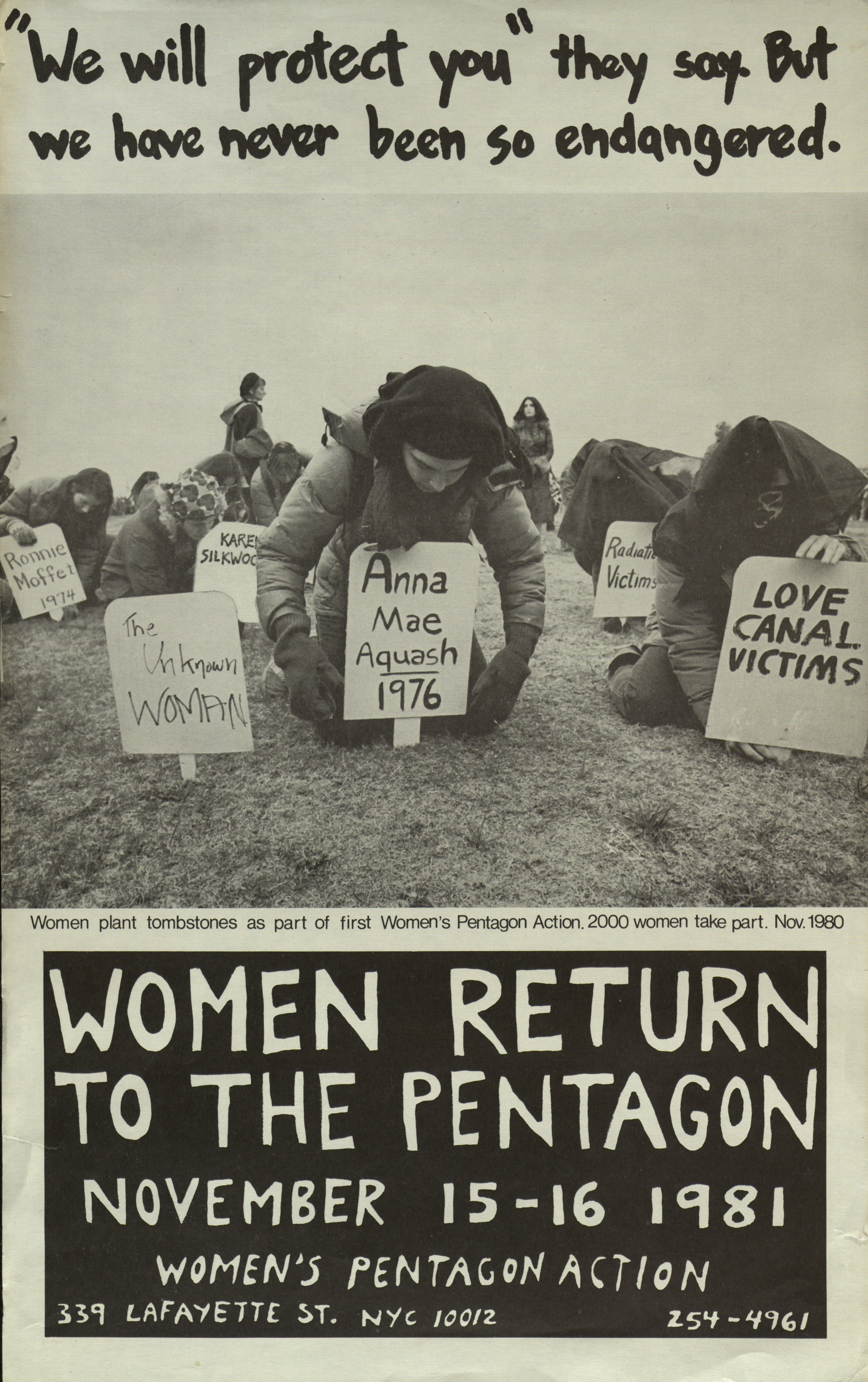

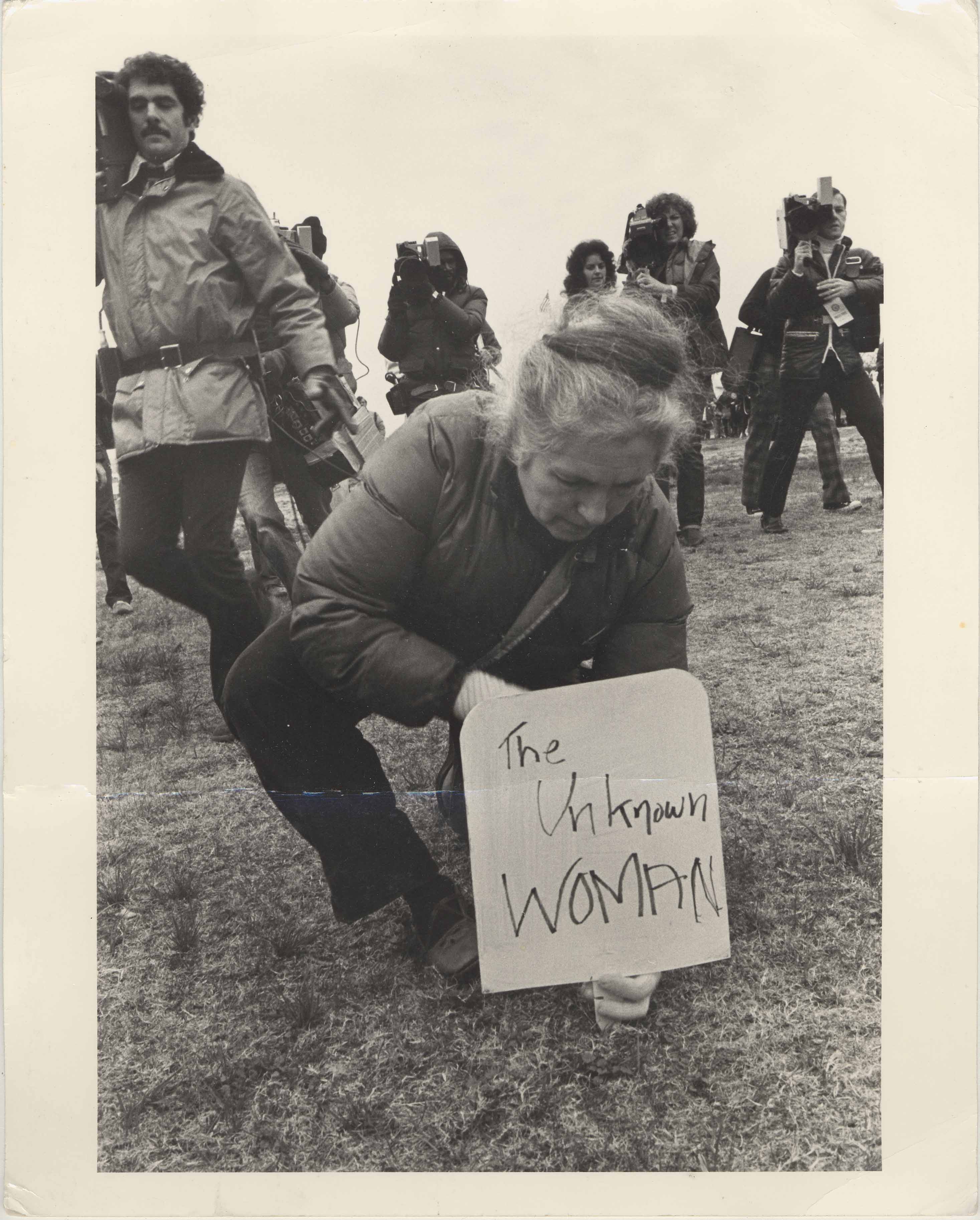

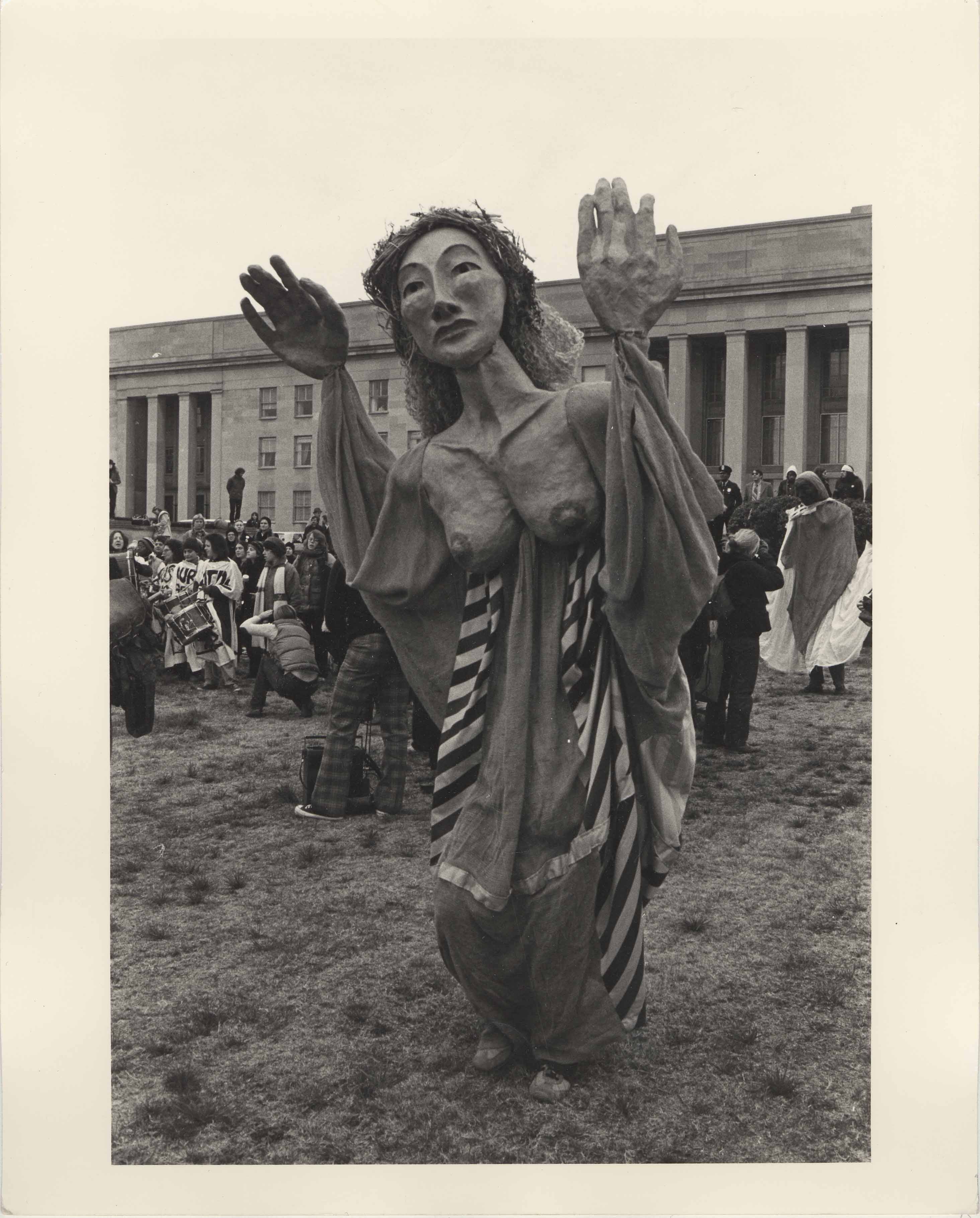

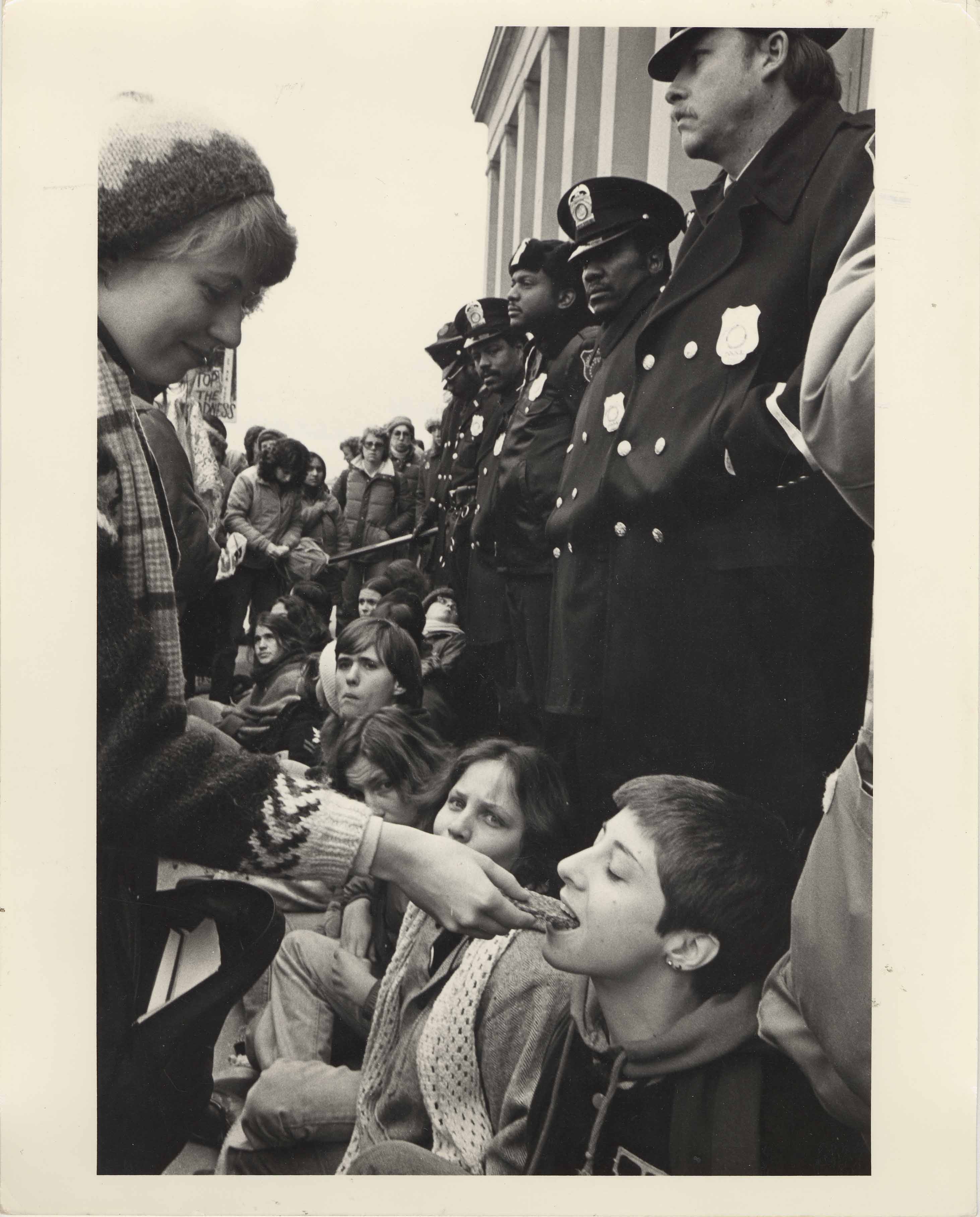

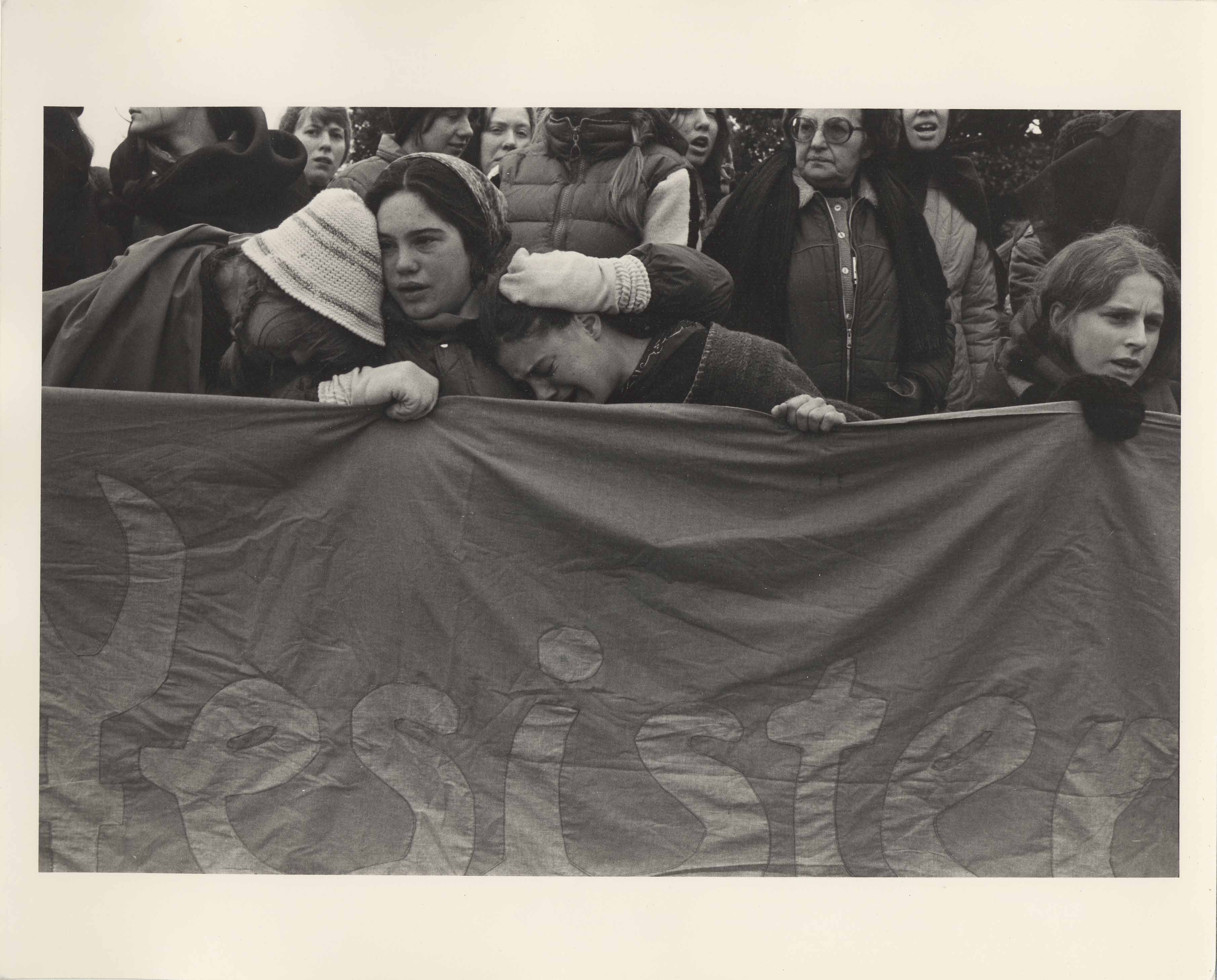

The Women’s Pentagon Action (WPA) was an east coast organization founded in the late 1970s by radical feminists who connected the issues of feminism with a gendered analysis of ecology, peace, and militarism. When the U.S. government announced plans to deploy a new generation of nuclear missiles in western Europe capable of reaching Soviet soil within minutes, nuclear war seemed imminent. In response to this escalation in U.S. nuclear policy, feminists organized two protests (in November of 1980 and November 1981), during which hundreds of women surrounded the Pentagon military complex (in Washington, D.C.), attempting to close or disrupt “business as usual.” The members and supporters of the WPA came from women’s liberation groups, were radical feminists, lesbian feminists, peace activists, and ecofeminists.

Street theater, with large puppets and mock tomb stones erected on the front lawn of the Pentagon were some of the powerful tactics employed by the protestors. Women encircled the Pentagon and closed the front gates with string, which symbolized the web of connectedness between all living things that would be destroyed in a nuclear war. Supporters of the WPA wrote one of the first feminist statements connecting the patriarchal oppression of women with war and environmental destruction. Their “Unity Statement” represented the voice of all women and emphasized outrage at the government’s militarism and nuclear policies that threatened all human life and health of the planet. This feminist-organized nuclear protest inspired women around the country, as well as women in Great Britain, to protest U.S. nuclear policies. Notably, two women who attended WPA events returned to England and went on to participate in the organization of the Greenham, England U.S. Air Force base protest. Many women from WPA later took part in the protests at the Women's Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice in Romulus, New York (see below).

Women’s Pentagon Action Records, Swarthmore College

Peace Collection

Harriet Hyman Alonso. Peace as a Women’s Issue.

Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, 202-210, 221-222. Print.

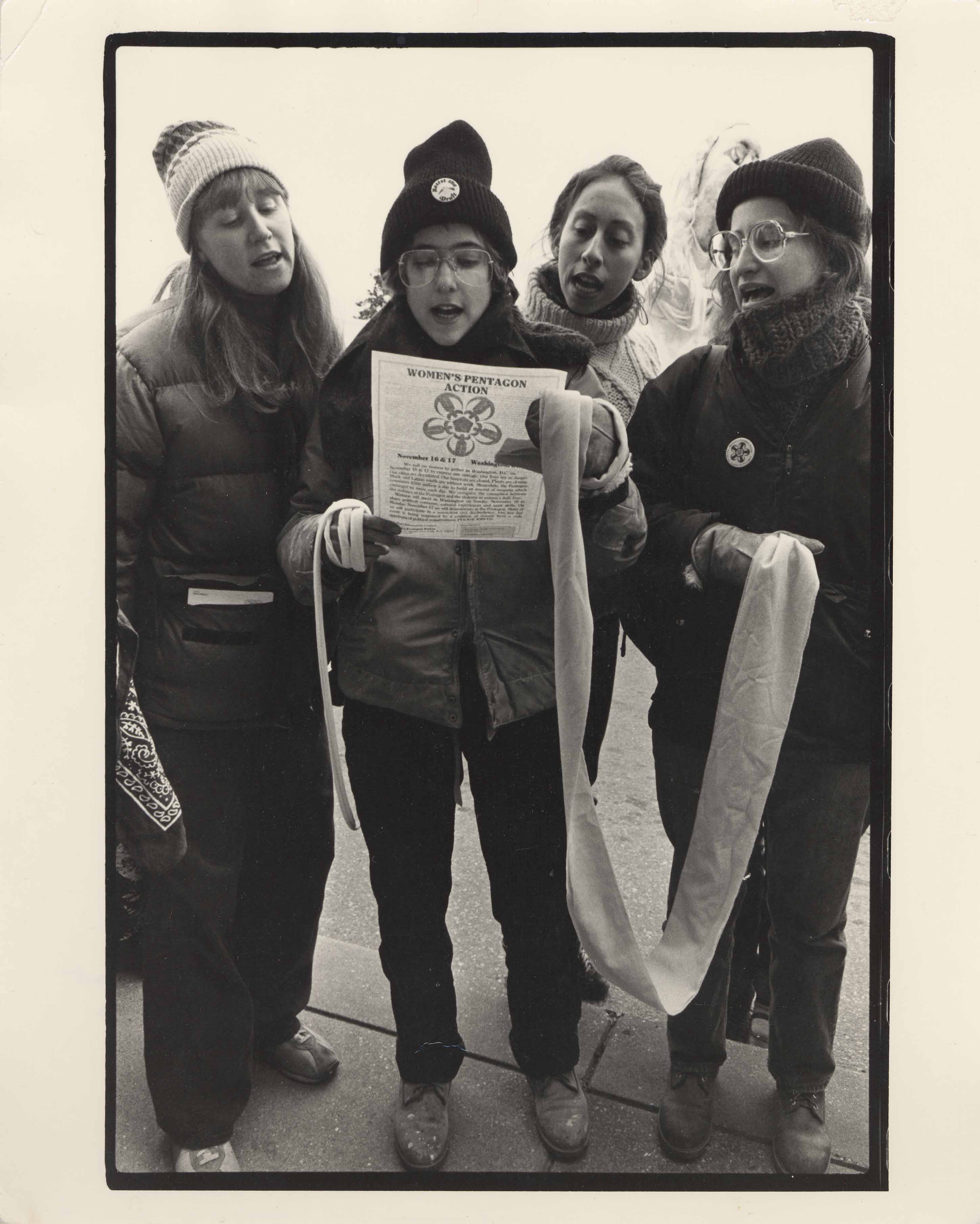

Reading the "Unity Statement"

Event: Women’s Pentagon Action, Pentagon

Washington, D.C.

November 16-17, 1980

Prints D 1030 - D 1042

6.5" x 9.5"

Version

of WPA's "Unity Statement"

Grace Paley

Event: Women’s Pentagon Action, Pentagon

Washington, D.C.

November 16-17, 1980

Prints D 1030 - D 1042

6.5" x 9.5"

Event: Women’s Pentagon Action, Pentagon

Washington, D.C.

November 16-17, 1980

Prints D 1030 - D 1042

6.5" x 9.5"

Event: Women’s Pentagon Action, Pentagon

Washington, D.C.

November 16-17, 1980

Prints D 1030 - D 1042

6.5" x 9.5"

Event: Women’s Pentagon Action, Pentagon

Washington, D.C.

November 16-17, 1980

Prints D 1030 - D 1042

6.5" x 9.5"

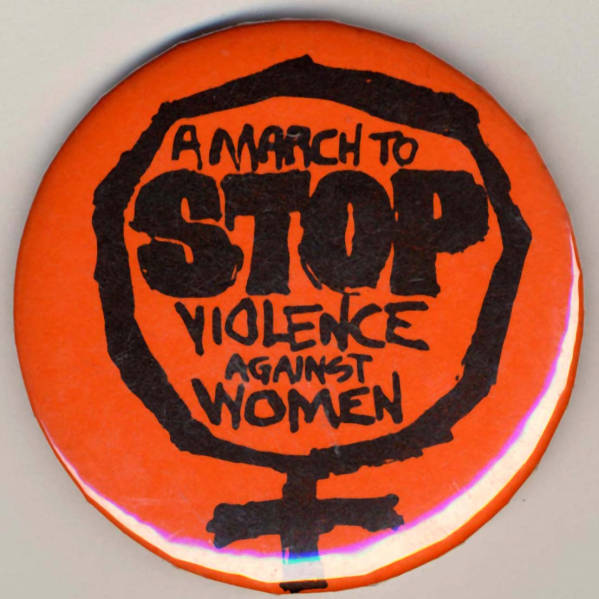

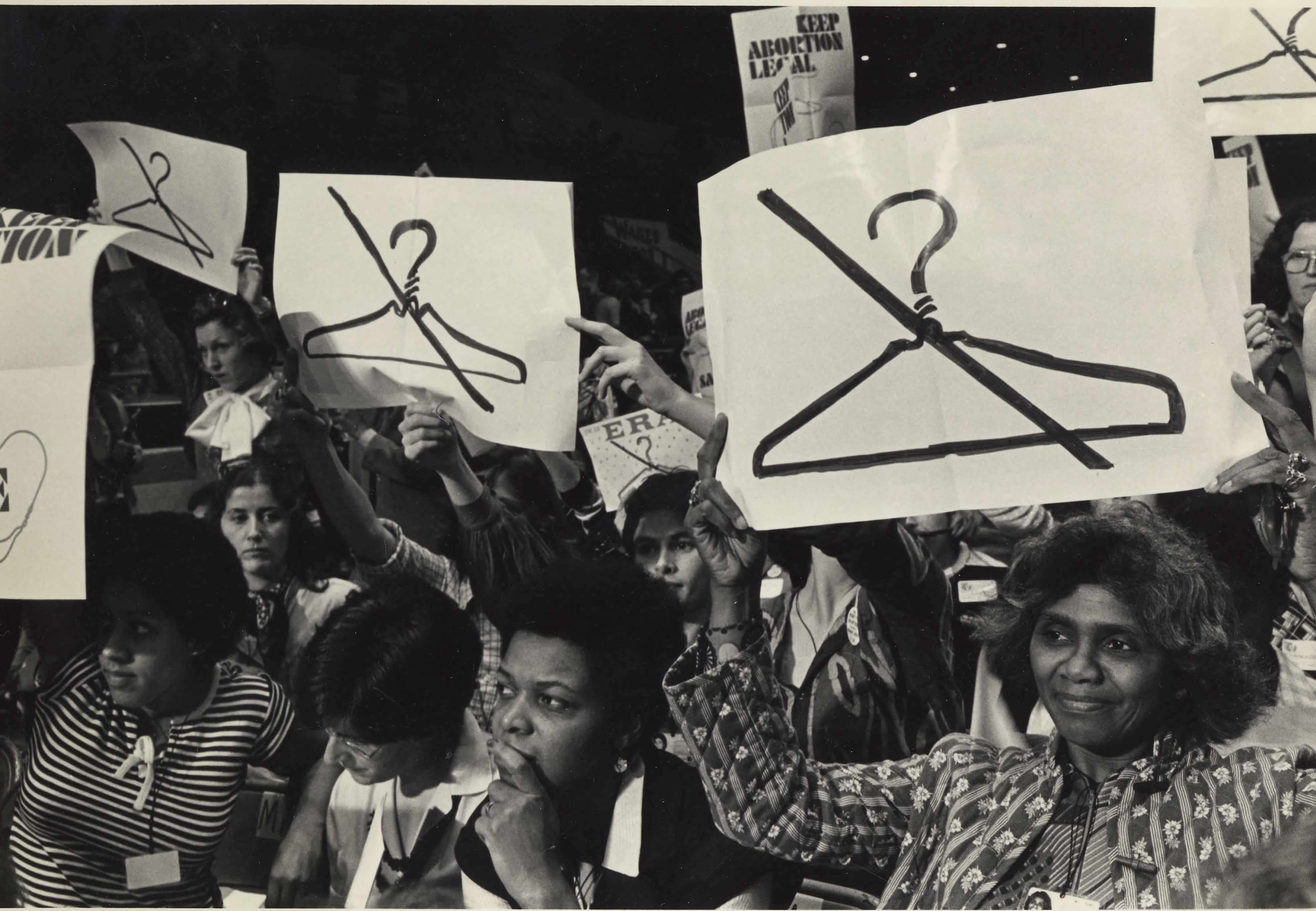

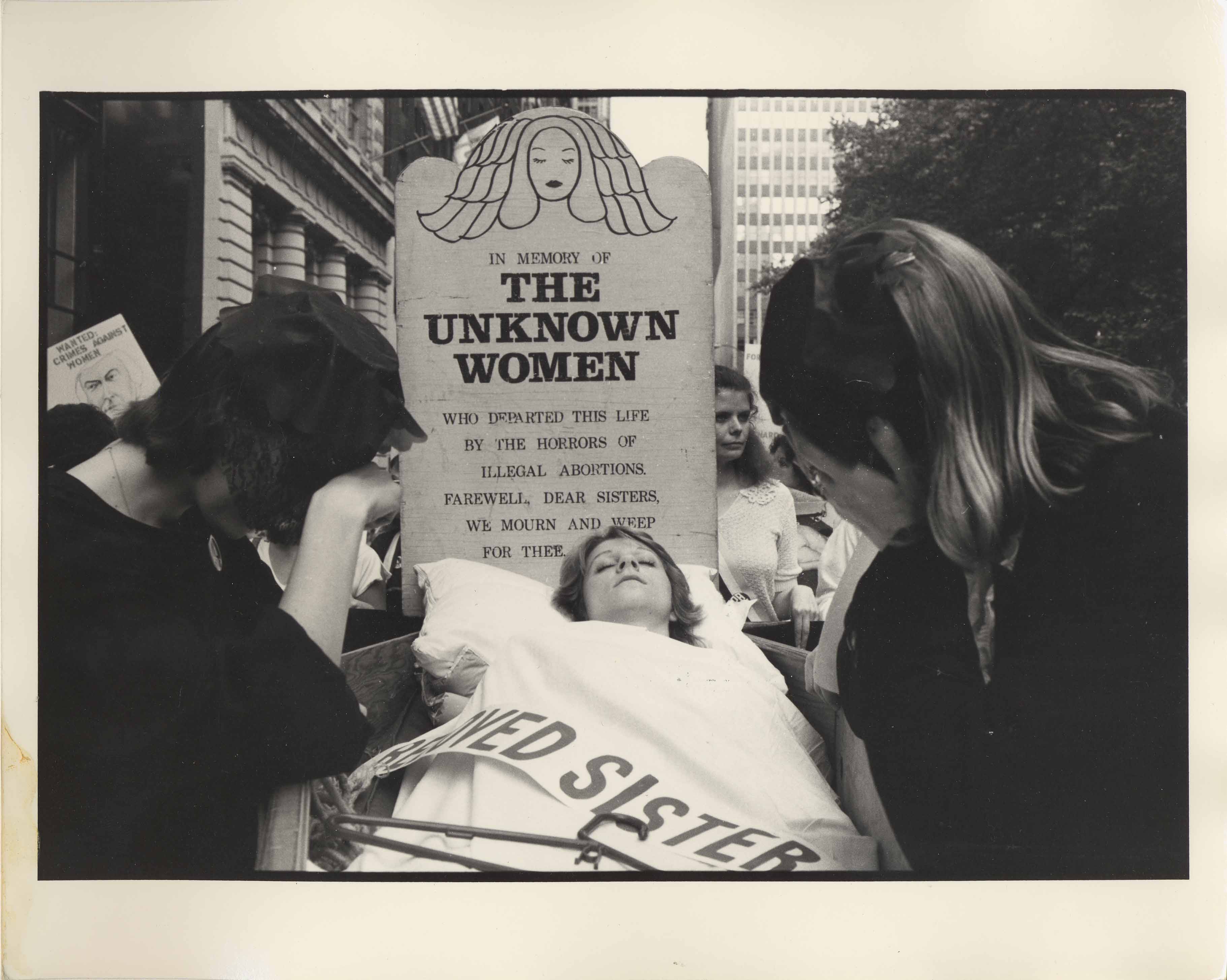

Event: Abortion Rights, March and Rally

Cherry Hill, New Jersey

July 17, 1982.

Prints D 1170 - D 1172

6.5" x 9.5"

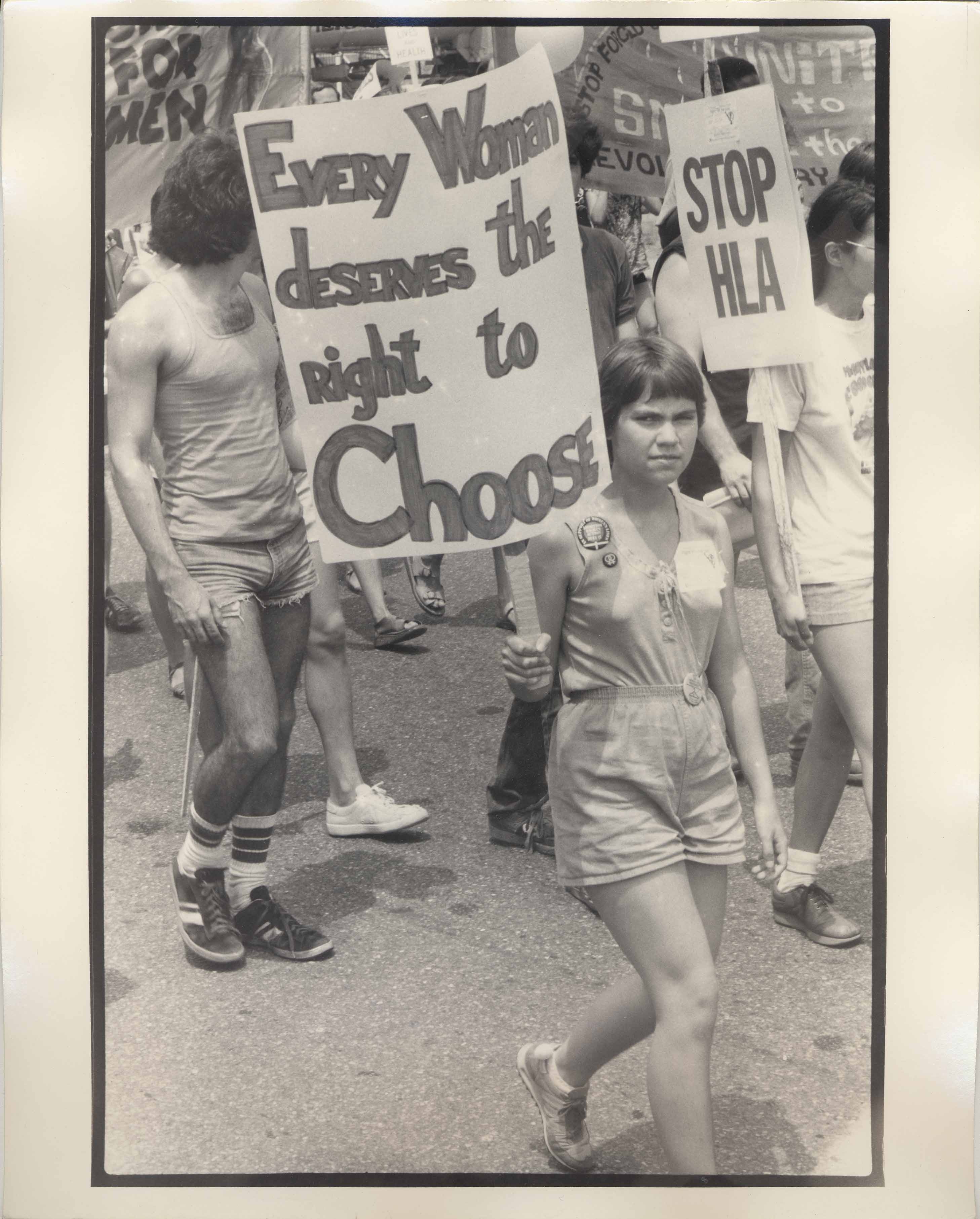

"Every Woman Deserves the Right to Choose" Event: Abortion Rights,

March and Rally

Cherry Hill, New Jersey

July 17, 1982

Prints D 1170 - D 1172

6.5" x 9.5"

The Seneca Army Depot located in Romulus, New York was a

transshipment facility housing short-range nuclear missiles destined

for deployment in western Europe. Protests by peace activists at

the facility began in the early 1980s. By 1983, feminist peace

activists planned for a summer-long series of protests at the Army

Depot. The women were in part inspired by the 1981 march, and

subsequent long-term women’s camp protesting at the U.S. Air Force base

at Greenham Common, England.

The Seneca Army Depot located in Romulus, New York was a

transshipment facility housing short-range nuclear missiles destined

for deployment in western Europe. Protests by peace activists at

the facility began in the early 1980s. By 1983, feminist peace

activists planned for a summer-long series of protests at the Army

Depot. The women were in part inspired by the 1981 march, and

subsequent long-term women’s camp protesting at the U.S. Air Force base

at Greenham Common, England.

In the summer of 1983, thousands of women from diverse backgrounds

and various peace and feminist organizations came together to set-up an

all-women’s peace camp on purchased land next to the Depot in

Romulus. These feminists connected militarism with a patriarchal

assault on the environment and human life. The peace camp was

known to the activists as “Seneca”.

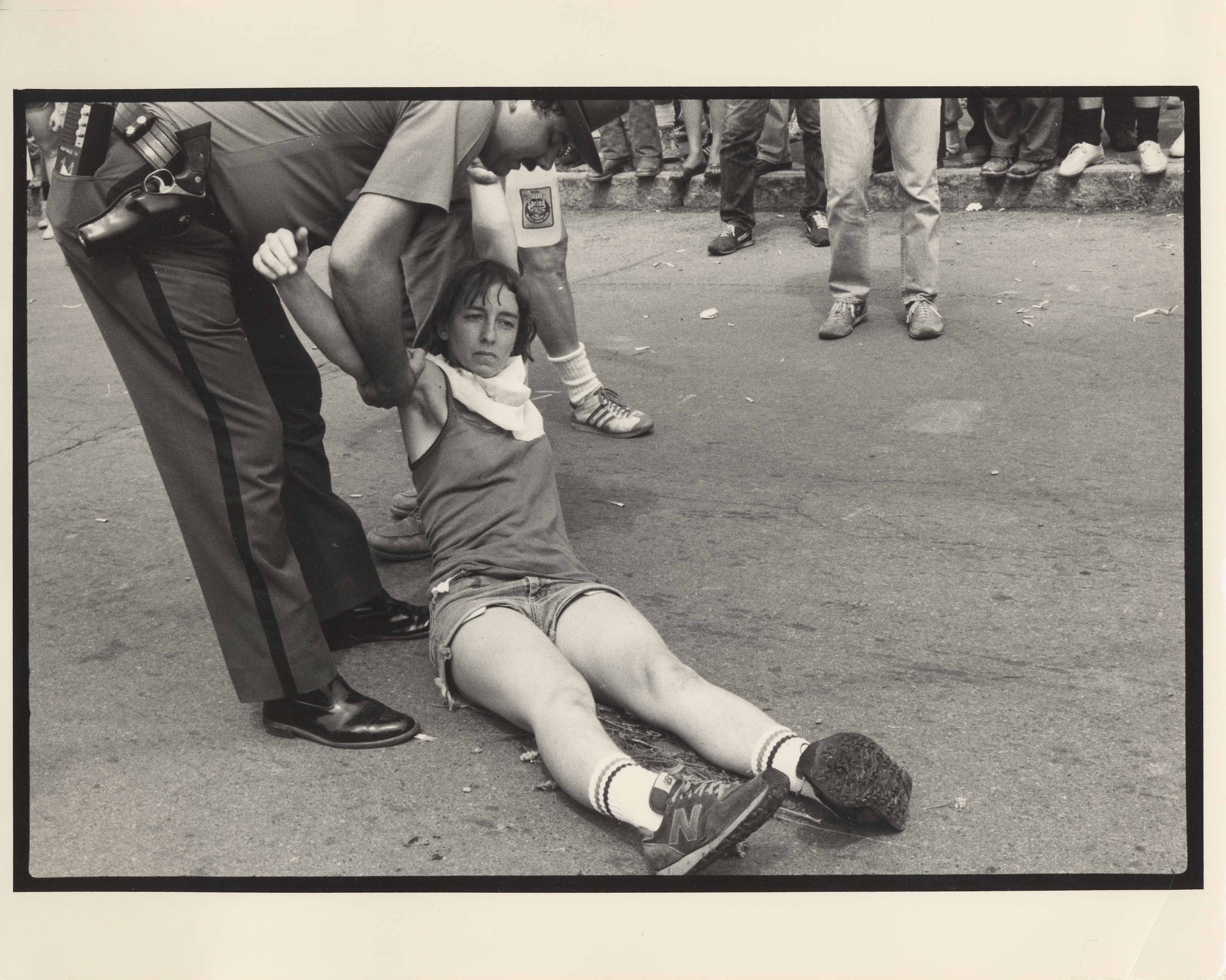

Women went to the

Seneca peace camp both to protest nuclear missiles and to live in

feminist community. They valued environment, peace, cooperation,

and unity and saw the possibility of creating an alternative to male

patriarchal and militaristic society. Protests included jumping

fences to invade the Seneca Army Depot base itself and directly challenging the U.S.

military with a constant oppositional presence.

The sense of community

fostered at Seneca had a lasting impact for many of the women who spent

summers at the peace camp. The camp, drawing in

thousands of women for a few days or forthe whole summer was run

cooperatively; all of the women were responsible for maintaining

sanitation, food preparation, and logistics. The protests,

political discussions, and community building inspired many women to

carry their feminism and political activism into many other

arenas. Women remained at the camp protesting the nuclear weapons

throughout the 1980s.

In 1995, the encampment

was turned into a retreat center and women’s community called Women’s

Peace Land. As of 2010 Women’s Peace Land reverted to the local

county government for unpaid back taxes. The Seneca Army Depot

closed in 2000 and the land was transferred to the Seneca County

government.

Literature cited:

Wendy E. Chmielewski, “Resisting Nuclear Madness: The Utopian

Vision of the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice,”

[unpublished paper], Rutgers Center for Historical Analysis, 2001.

For more information, please visit Swarthmore

College Peace Collection Resources:

http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/peacewebsite/scpcWebsite/Documents/

ResourcesPeaceHistory.htm#Womens

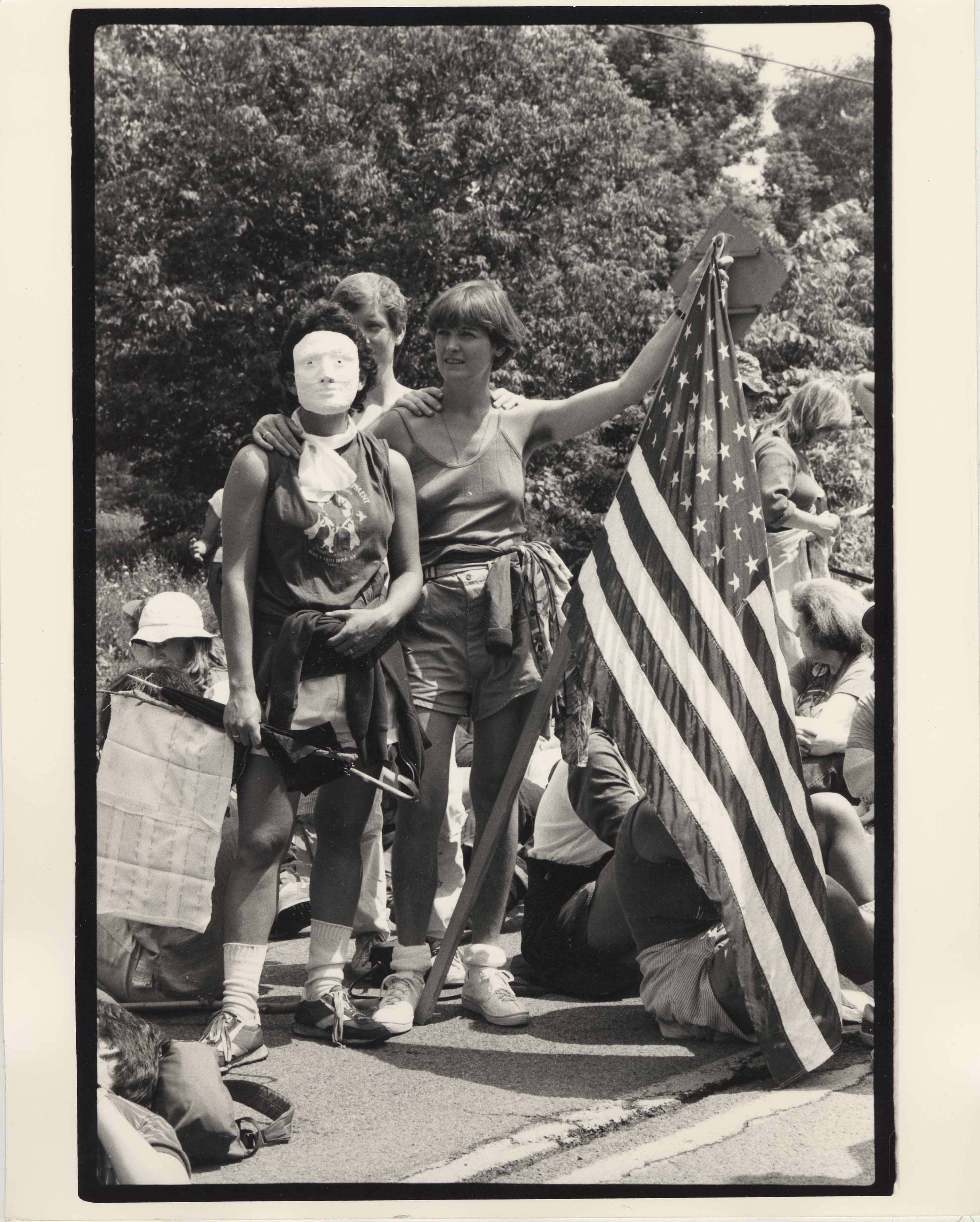

Event: Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice

Seneca Army Depot, Romulus, New York

August 1, 1983

Prints D 1250 - 1274

6.5" x 9.5"

Event: Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice

Seneca Army Depot, Romulus, New York

August 1, 1983

Prints D 1250 - 1274

6.5" x 9.5"

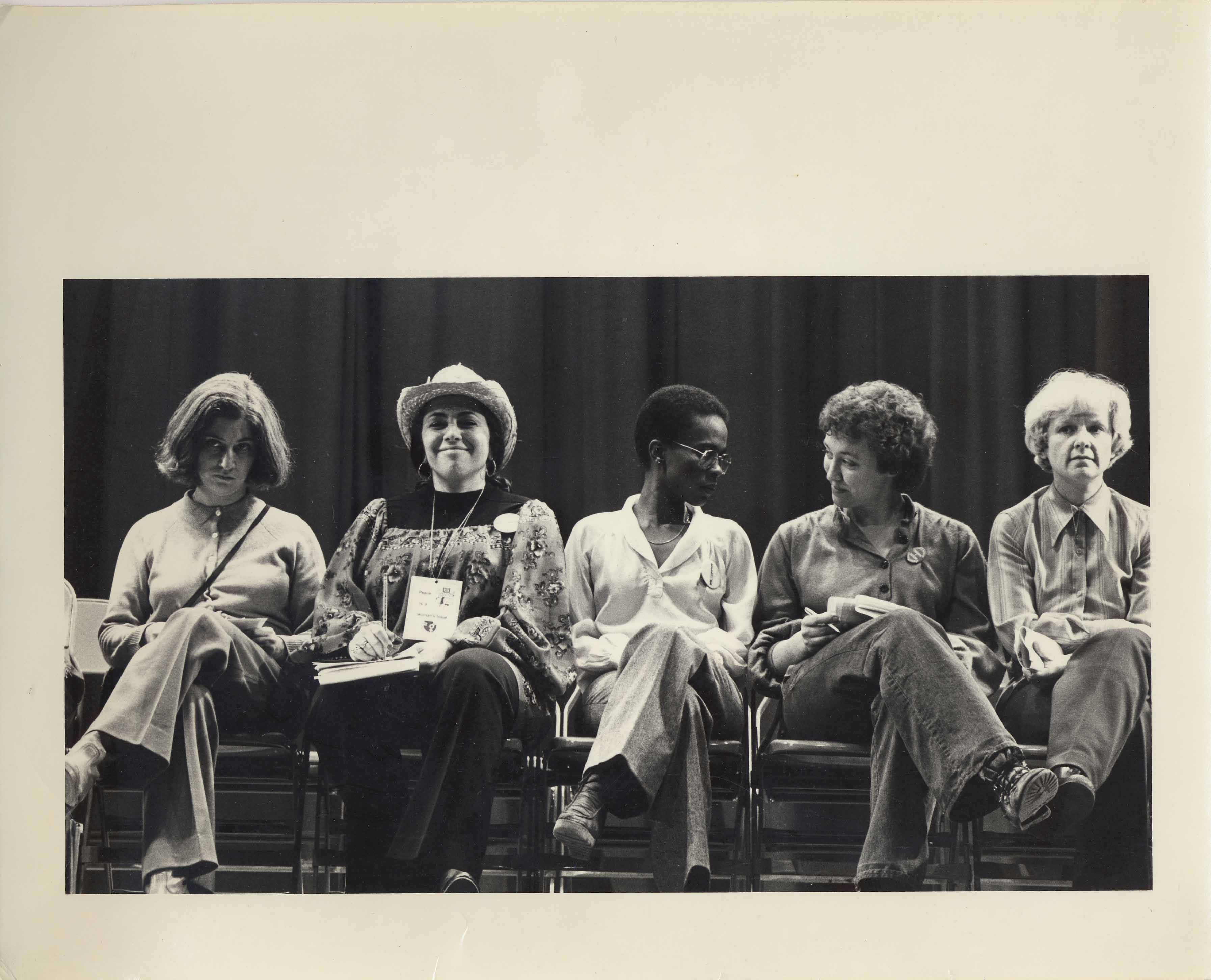

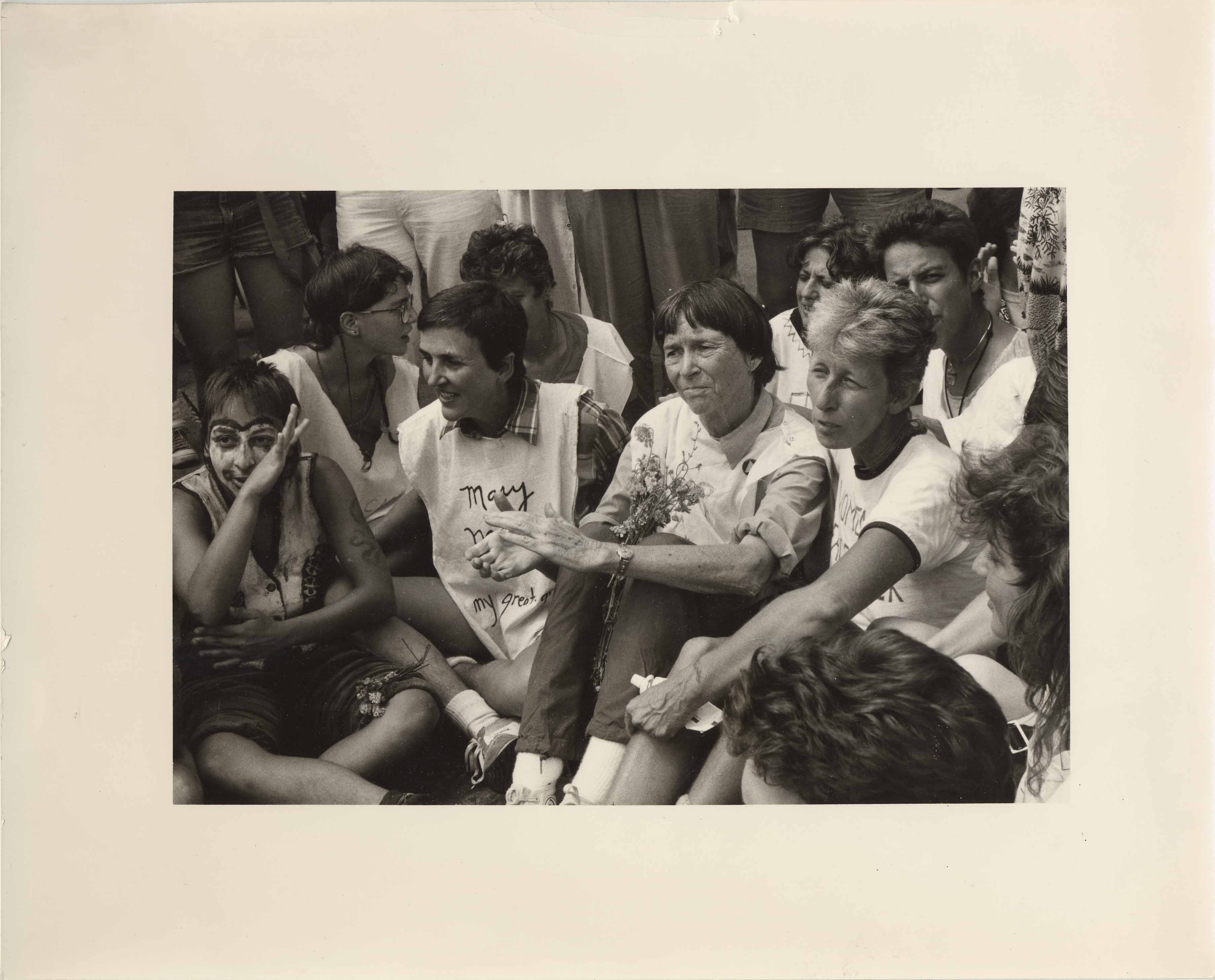

Barbara Deming (seond from right), Blue Lundi (far right)

Event: Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice,

Seneca Army Depot, Romulus, New York

August 1, 1983

Prints D 1250 - 1274

7.5" x 9.5"

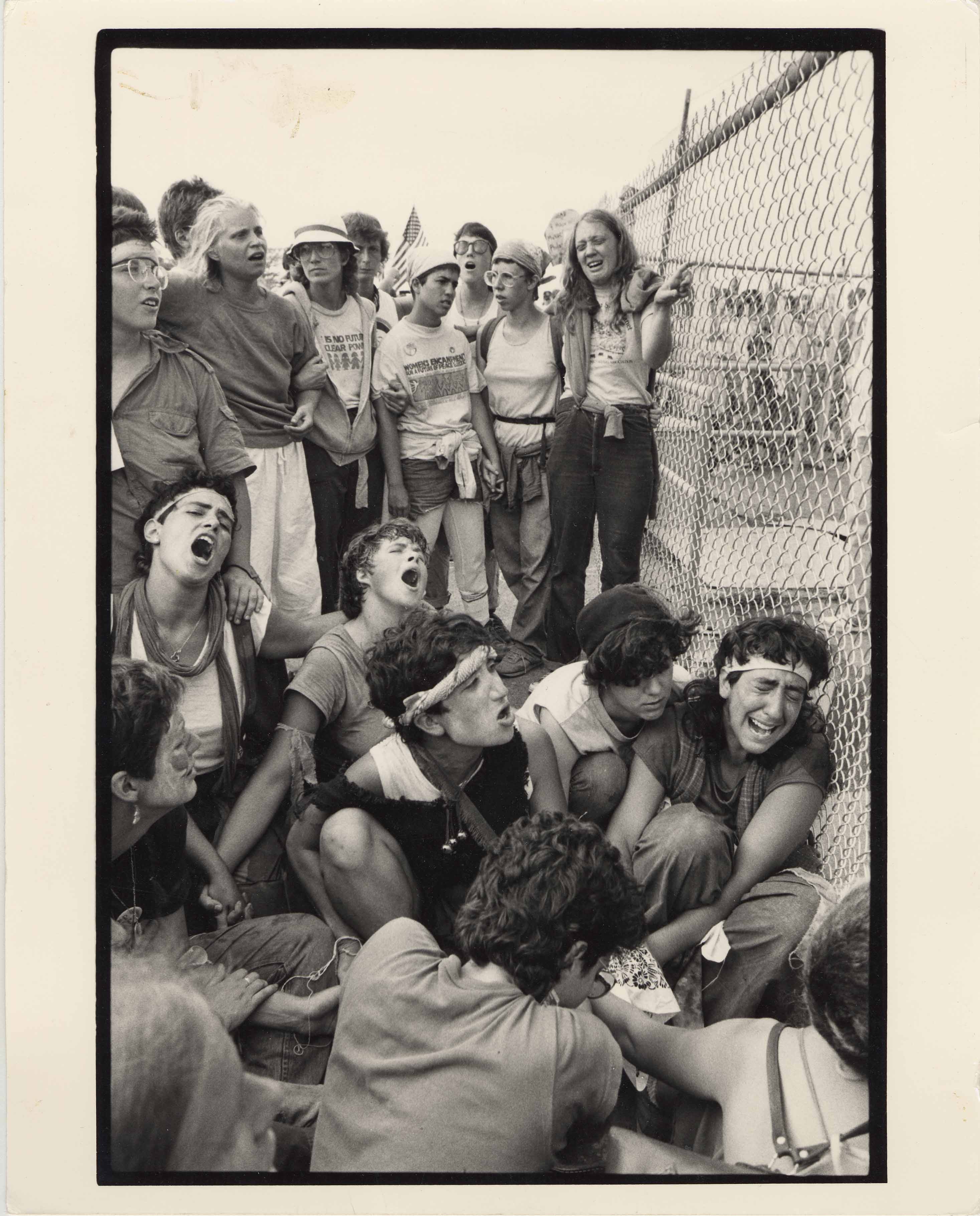

Event: Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice,

Seneca Army Depot, Romulus, NY

August 1, 1983

7.5" x 9.5"

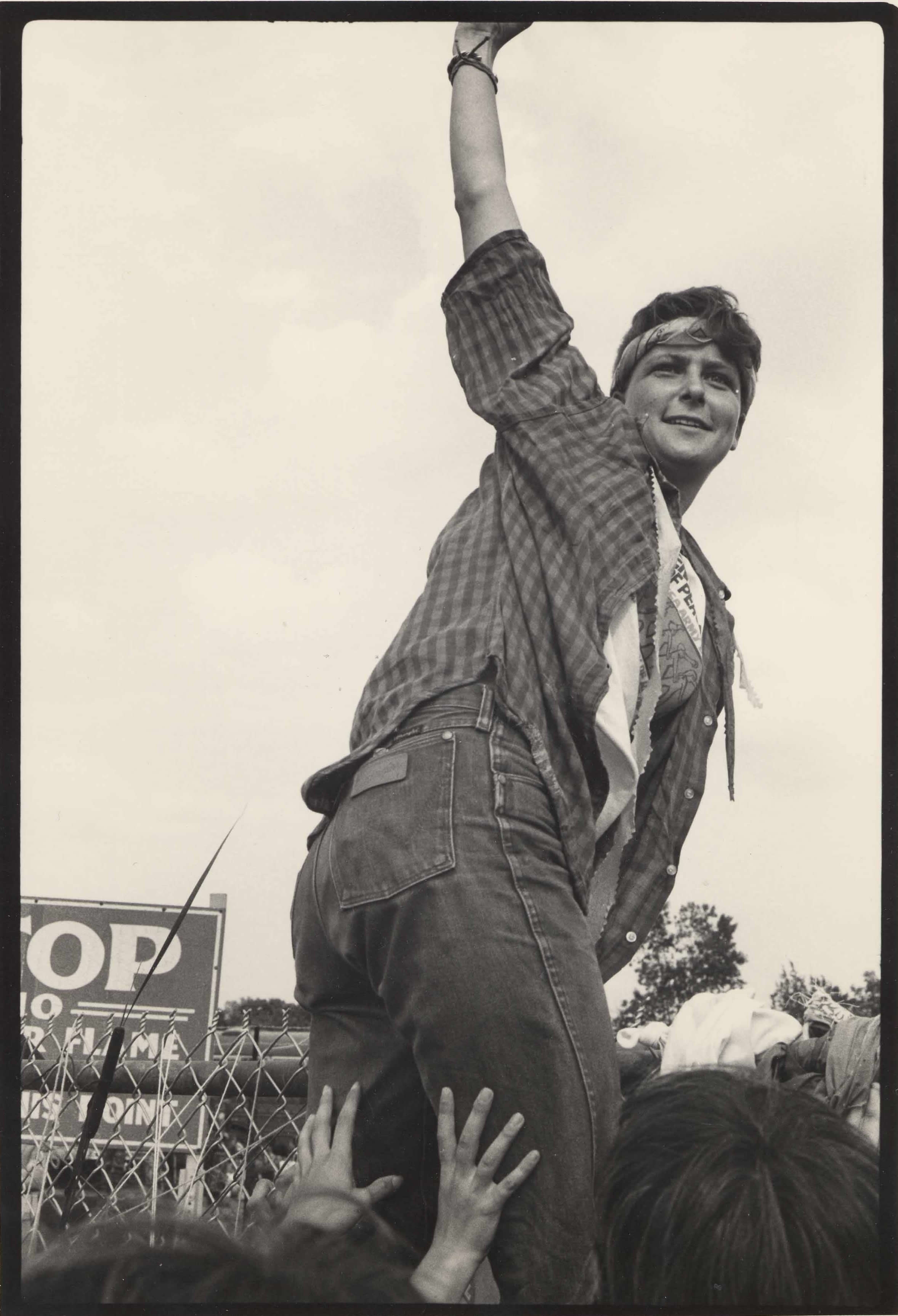

Event: Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice,

Seneca Army Depot, Romulus, NY

August 1, 1983

6" x 9.5"

Created March

2010 by Elizabeth Matlock and Wendy Chmielewski

This file was last updated on

February 20, 2015